The General Social Survey asked two questions about regular smoking -- do you regularly smoke now (SMOKE), or if you don't now, did you ever regularly smoke in the past (EVSMOKE). Adding the "Yes" answers for both together, and taking them as a percent of everyone asked about smoking, we can find out who has ever been a regular smoker in their life -- past or present.

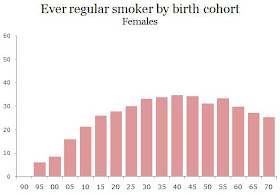

Here is the percent of ever-regular-smokers within 5-year birth cohorts, shown by the first year of their group. So "90" means 1890-94, "15" means 1915-1919, etc. I've split them into males and females because their history of adoption and abandoning of smoking is different (something I hadn't thought of at first).

The first two male cohorts don't have huge sample sizes, so I wouldn't make much of the jump in the 1895-99 group. Males born around the turn of the 20th century already started with a high chance of ever taking up smoking during their lives, around 40%. That rose to a plateau of just under 50% for men born between 1925-39. Already by the cohort of the earlier '40s there is a decline, and that only plummets in each cohort after.

Women, by contrast, started this period out very unlikely to ever get into smoking. That changed with the Jazz Age, which began around the mid-1910s, about the time that girls born around the turn of the century would be teenagers and be exposed to a whole new set of role models. Although it was born of that time, the glamor of female smoking outlived the Roaring Twenties. The cohort most likely to regularly smoke at some point was the 1940-44 group. After a half-century of steady growth, the first decline comes with the 1945-49 group, which only falls further with each one after. There is a jump in the late '50s cohort, though -- maybe when they were young teenagers during the Counter-Culture, smoking became briefly fashionable again for girls (not for boys, according to their graph).

Since the cohorts are fairly large, breaking them up into single-year groups still leaves sample sizes over 100. To pinpoint when the declines began, for males it looks like the 1941 cohort, and for females the 1947 cohort.

The first cigarette warning labels came in 1966 and have remained since. By that time, the 1941 cohort of males had already started to give up trying smoking in their teens and early 20s, when most people who ever become regular smokers begin. I also doubt it was the earlier famous 1954 British Doctors Study linking smoking and lung cancer -- hardly any 13 year-old American boys would've heard about it.

For females, it's a little more plausible that the warning labels had an effect, since the 1947 cohort would've been 19 when they came out, still having some of their vulnerable period left. We can definitely rule out the academic studies from the '50s, since they would've been 7 when the famous one came out.

Still, we should prefer one cause to two. The labels can only possibly explain the female decline, requiring some separate cause for the male decline. The disappearance of cigarettes seems so close in both groups that we should just treat it as one change, just like when men and women both got scared of dietary fat and began eating more carbohydrates.

What that cause is, I don't know. It's not related to my usual stories about rising or falling crime rates. But it is worth noting that two "obvious" answers -- a huge study linking smoking and lung cancer, and dire warnings right there on the package -- are wrong. That doesn't surprise me, since those are both top-down influences, and those cannot change people's attitudes so dramatically and for so long. (And it's clear that this is an attitudinal change, not some lame economic change.)

In fact, since the warning labels came after the decline was already in progress, we see yet another case of the top-down solution being a mere delayed and symbolic reaction by the technocracy. The experts, whether in the government, academia, private sector, or whatever, just jump on the already-rolling bandwagon and shamelessly try to hog the credit for having set it in motion.

It could be as simple as a fashion cycle, where no external factors are needed to explain the rise and fall pattern. It would be just like an epidemic. That would be a local, bottom-up explanation, and those tend to pan out.

I don't like "fashion cycle" explanations when a bunch of cycles all fit on top of each other, like the ones I've been looking at for awhile with crime rates, etc. But if there isn't some other cycle to link it to, I'm OK with treating cigarette smoking as a fashion that came and went. There may well be some other collection of cycles that fit with the smoking cycle, and I'll keep my eyes peeled. For now, though, I have no clue. Someone else should look into it, though. But something that changed at the grassroots level, not some ineffectual policy or campaign by outsiders.

* As an aside, that's how real science gets done -- you're just playing with all kinds of different stuff, and some of it goes places you didn't intend. Blind variation, then selective retention. Starting with a question and collecting data that bear on it -- so-called "hypothesis testing" -- usually goes nowhere.

Some cool pattern could turn up in your data, but because you're in tunnel-vision mode when testing hypotheses, you'll miss what's right under your nose. You'll only think of it months or years later, when you're no longer thinking so narrowly about that project, just letting your mind wander. But why not start off that way, instead of wasting so much time with blinkers on?

First of all, your blog is gold. I always saw some kind of cultural change between the early 90s and current times, but I could never figure out what caused it. Thanks for outlining all this in such clear detail.

ReplyDeleteI believe you may be wrong about one thing, though.

e you ever considered that rising crime is caused by the proportion of high-testosterone men in the population?

Rising crme periods typically follow periods of peace and prosperity. As Roissy has pointed out, high-testosterone men have greater reproductive success during times of prosperity, because they are more competitive less cooperative. These traits are valuable when there is no external threat to a community, since community-members will then compete against one another("cocoon"), rather than pull together. It also explains the ower-level of trust in times of prosperity.

The younger generation is very high testosterone. This generation then comes of age and, being masculine and therefore creative and risk-taking, ushers in a new age of creativity, but also chaos and crime. People pull together again. In the new milieu, beta men - those of low-testosterone/high-estrogen - have greater reproductive success. Theare naturally more cooperative,

During times of crime and/or poverty, however, low-testosterone men have greater success, because they are more cooperative. High-testosterone men, on the other hand, have high attrition rates during these times, because they take great risks and are themselves prone to crime(and eventually being locked up/executed).

According to your theory, there are plenty of potential criminals out there, but they are not committing crimes. At the same time, you believe there are plenty of Millenials capable of creativity or working traditionally masculine jobs, they just choose not to because they don't have the motivation to - they don't have to, in other words.

What if, nstead, the Millenials, as a generation, had substantially less testosterone than the Baby-Boomer generation. This would be due to beta men have greater reproductive success during 60s-early 90s, due to alpha men having high attrition rates during times when cooperation and interdependence is necessary. Of course, there are plenty of high-testostorone men amongst the Millenials, just of quite lower proportion than existed in the Baby-Boomer population.

IF this theory is true, it means that Millenial women will disproportionately choose to have children with high-testosterone men. But it also means that crime rates - and the period of increased creativity - won't begin to rise for quite some time - until the children of the Millenials begin to hit puberty. As we know, the Millenials have not really begun having children in earnest quite yet, and may not for quite some time.

As one last comment, this would also explain why the American job market has become so bureacratic and focused on verbal intelligence. Contrary to popular belief, its not because of outsourcing. If it was, we wouldn't need to import immigrants to work traditionally masculine jobs - including professional jobs such as doctors and engineers, which are more ad more being filled by East Asians and Indians. Rather, the problem could be the lack of high-testosterone men amongst the Millenials...

ReplyDeleteI think if anything it looks the other way. High-T guys were the ideal with Clint Eastwood, Stallone, Schwarzenegger, etc. when crime rates were going up.

ReplyDeleteIn the mid-century, it was more Frank Sinatra than Bon Jovi, rock out with your cock out kind of music.

There's some paper due out soon by David Fessler et al, about how women's preferences for a dominant male tracks how anxious they are about crime.

I'm also hesitant to chalk up these changes to different genetic success. It's usually just one generation of rising or falling crime rates. Probably a norm of reaction, facultative adjustment, or that kind of thing.

Its hard to say for sure, but maybe it had something to do with all the anti-smoking campaigns that started in the 60s and 70s. Keep in mind before then it was only a "theory" that smoking caused bad health. Who knows, maybe 20 years from now they will refer to the delcine of current smoking to the electronic cigarettes effect.

ReplyDelete